THE ARCHIVES

Golden Eagle

Populations of Golden Eagle were depleted to near extinction in the UK as a result of persecution, degradation of habitat and contamination from organochlorine pesticides. The Roy Dennis Wildlife Foundation undertook the first extensive Golden Eagle satellite tagging study in the UK, and also assisted the reintroduction of Golden Eagle to Ireland.

Image: Laurie Campbell

About the Golden Eagle

Adult golden eagles are dark brown with a golden sheen on the top of the head and neck. Juveniles have a white base to their tail and white patches on the undersides of their wings, meaning they can sometimes be confused with the white-tailed eagle. However, the best diagnostic tool is the shape of the tail: distinctively wedge-shaped in white-tailed eagles but just slightly rounded in golden eagles. From a distance adults can also sometimes be confused with buzzards, however golden eagles are much bigger, with a wing span of up to 2 metres, almost twice that of a buzzard. The tail is also longer than a buzzard’s and the head protrudes more prominently in front of the wings. They have a yellow base to their powerful bill, and yellow legs and talons. In flight the wings are spread in a slight ‘V’ and the tips are spread like fingers.

Image: Laurie Campbell

Habitat and distribution

In Scotland they inhabit mountains, high moorlands and remote islands, but before persecution by man would have been much more widely distributed. The golden eagle has a very wide distribution, being found across much of the Northern Hemisphere. Within the UK its stronghold is Scotland, and is found mainly in the Scottish Highlands and islands. It has recently been reintroduced to Ireland,

but remains absent from Wales and is found only in very small numbers in northern England.

DIET

Golden eagles take a range of prey items, both birds and mammals. Most commonly they feed on medium-sized prey such as rabbits, hares, grouse and ptarmigan, but also take young deer, as well as scavenging on carrion. Pine martens,, foxes, water voles and adders have also been reported as prey items.

REPRODUCTION

Golden eagles do not usually breed until 4 years of age or more. An eyrie built of sticks is

constructed on a remote cliff ledge or in the top of a mature tree, although they prefer to use existing nests. Eyries are huge structures, frequently being at least 2m wide and deep. The female lays 1-2 eggs in late March-early April and incubates for 43-45 days. The male shares incubation but it is mainly carried out by the female. There is normally a noticeable size difference in the chicks due to the eggs being laid over a few days, and the older chick may kill its younger sibling, especially when food is scarce. Both adults feed the chicks and the young fledge after about 65 days. They continue to be fed for a further three months or so, and then leave their natal territory sometime in the autumn or winter. Young eagles roam widely in their first years of life, before finding a vacant territory and mate. They are monogamous and mate for life.

Status and threats

Golden eagles are classified by the World Conservation Union (IUCN) as ‘Least Concern’. However, although they are widely distributed across the globe, they have suffered huge declines due to persecution and, sadly, this continues today, with poisoning being the most common form of killing. As with many other raptors, golden eagles were badly affected in the 1950s and 1960s by organochlorine pesticides such as DDT, which caused thinning of eggshells and so caused a huge decrease in reproductive success. Within Scotland many former territories remain uncolonised, mainly due to illegal persecution and in parts of the Western Highlands due to ecological degradation and reductions in food availability.

Within the UK they are strictly protected under Schedule 1 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 and The Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004. They are also included on the Amber List of UK birds of conservation concern. It is an offence to intentionally take, injure or kill a golden eagle or to take, damage or destroy its nest, eggs or young. It is also an offence to intentionally or recklessly disturb the birds close to their nest during the breeding season. Violation can result in a fine of up to £5000 and/or a prison sentence of up to 6 months.

THE ARCHIVES: 2007

Understanding the cultural behaviour of Eagles through satellite tracking

Golden eagles in Scotland have already been affected by human disturbance and it is known that eagles have abandoned nesting sites because they are too close to walking routes which have become progressively popular. This must be considered within a culture of long term human persecution of eagles. Golden eagle behaviour has evolved to avoid humans at as great distance as possible. This behaviour is reinforced in the young by them being reared without sighting humans.

Evidence from ospreys in Scotland already shows that, without persecution, individuals become more used to people passing by regularly at a safe distance, and this distance is becoming less. This leads to the view that young birds, which are reared in nests where they can view people without threat, are more able to breed at new nest sites within human-used landscapes.

This satellite tracking study analysed the behaviour of Golden Eagles, comparing areas with different remoteness in accordance with the cultural change in human behaviour. The results were fascinating, and hugely supportive for future efforts to restore the population of Golden Eagles in Scotland and the UK.

Image: Mike Crutch

Caingorms

The project began in the Glenfeshie Estate in the Caingorms

18 Eaglets

13 males and 5 female eaglets were satellite tagged throughout the project.

2007

The first satellite tag was fitted to an eagle chick in 2007, the first time a Golden Eagle had ever been satellite tracked.

Project partners

The initial project was a partnership between the Cairngorms National Park Authority, Scottish Natural Heritage, Glenfeshie Estate and the Roy Dennis Wildlife Foundation.

Snippets from the data

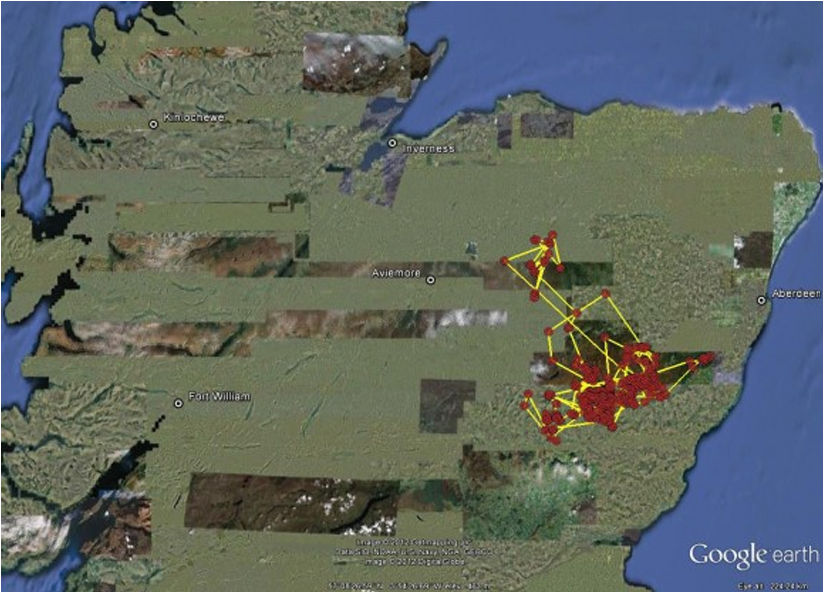

Angus 26

Angus 26 moved away from his natal site on 15th October. He remained in Angus/Aberdeenshire until early December, and then flew to Glenlivet. The image above shows his movements in 2011.

Angus 33

Angus 33 (Angus 26’s brother) first travelled away from his nest site on 12th October. He travelled to Abernethy on 21st October but returned home again. In early December he headed to the Glenlivet area and in 2012 has been ranging around the central Highlands. The image above shows his movements in 2011.

Calluna

Calluna remained within her parents’ homerange throughout 2011.

Canisp

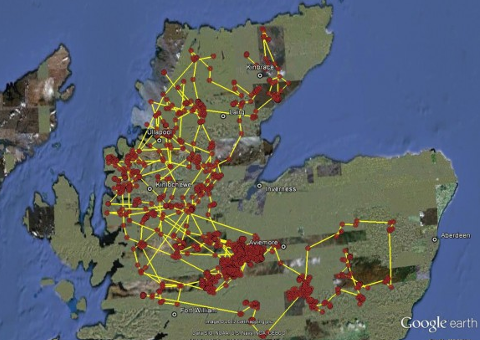

Canisp fledged on 2nd August 2011. She has ranged throughout northwest Sutherland but regularly returns to her parents’ homerange. The image above shows her movements in 2011.

Corrie

Corrie fledged from the nest on 17 July 2010. Movements within the initial month out of the nest were within one square km around the eyrie; from mid August he wandered a little more in a range of 10 square km. He increased his range to 1250 square km in September, and started making longer trips in October, regularly retuning to his parents’ range in Sutherland. He spent the rest of 2010 exploring Sutherland and Wester Ross

Eaglet 106

After fledging in July 2010, Eaglet 106 remained within her parents’ home range in the Flow Country for the rest of the year, even though her brother (Eaglet 107) departed in late October. In February 2011 she finally set off on her travels. She headed up past Ullapool and then to Wester Ross and Drumochter, before heading south to the Cairngorms. She then remained around North Perthshire and the Monadhliaths throughout the summer, then began to range more widely again, heading back off to Wester Ross in September. She continued to range extremely widely throughout the rest of the year, moving between Sutherland and the Monadhliaths with several longer flights. The image above shows her movement in 2011.

THE ARCHIVES: 2005

Reintroducing Golden Eagle to Ireland

The Roy Dennis Wildlife Foundation supported the Irish reintroduction of Golden Eagle by assisting with feasibility studies in Glenveagh National Park and then later on by helping with the collection of chicks in the Highlands, the feeding and holding of the young before transfer to Ireland, the export paperwork as a Balai Directive licensed premises and the fitting of radios and wing-tags in Donegal. The first Irish pair successfully bred in 2007.

Irish project manager Lorcan O’Toole collecting a Scottish eaglet for translocation